First Impressions: Navigating Grief in “The Boy and the Heron”

Hayao Miyazaki, a perennial figure in the animation world, has maintained a consistent artistic style and a penchant for fantasy storytelling since his debut in the late 1970s. Despite announcing his retirement after The Wind Rises in 2013, Miyazaki returned to the film industry by initiating the production of The Boy and the Heron in 2017, offering audiences another enchanting glimpse into his colorful world. The film, released globally on December 9, 2023, is a manifestation of Miyazaki’s enduring creativity, providing viewers with a sense of comfort through his unique animation style.

Miyazaki’s decision to create The Boy and the Heron before potentially departing from the film industry was motivated by a desire to leave behind a cinematic legacy. In 2017, Studio Ghibli producer Toshio Suzuki mentioned that Miyazaki wanted to show his grandson the lasting significance of this film as he moves on to the next chapter of life. Beyond its magical narrative, the film serves as an imaginative exploration of grief, joy, and the profound choices we encounter in life’s journey.

Growing Pains

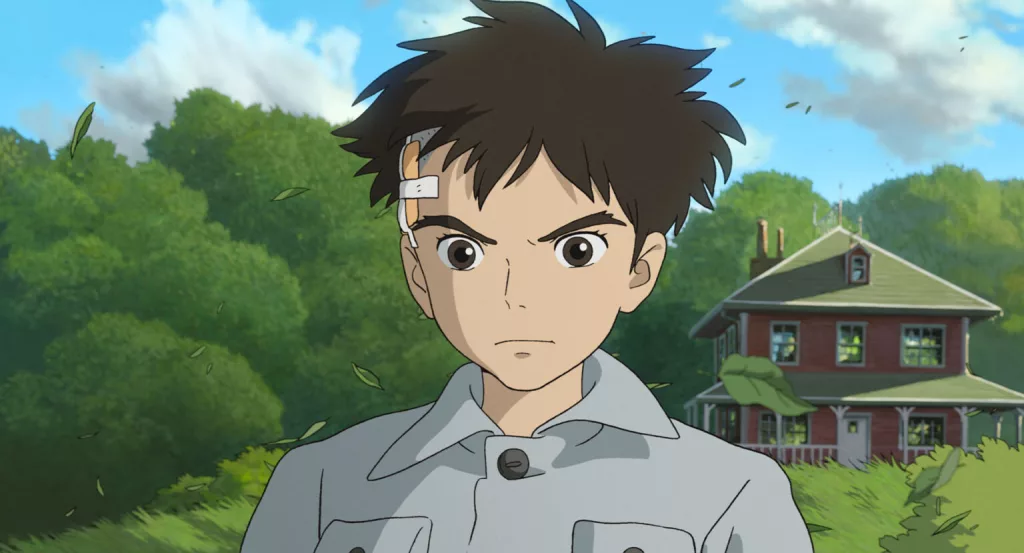

The narrative of The Boy and the Heron unfolds amid a backdrop of death, with a moonlit Tokyo cityscape during World War II. The scene is marred by the flames of a burning hospital, the workplace of Mahito’s late mother. Following the loss of his mother in the hospital fire, Mahito’s life undergoes significant changes as his father and his deceased mother’s sister anticipate a baby. This series of events prompts Mahito’s move to the countryside, where he grapples with the challenges of adapting to a new environment and integrating into his unfamiliar school.

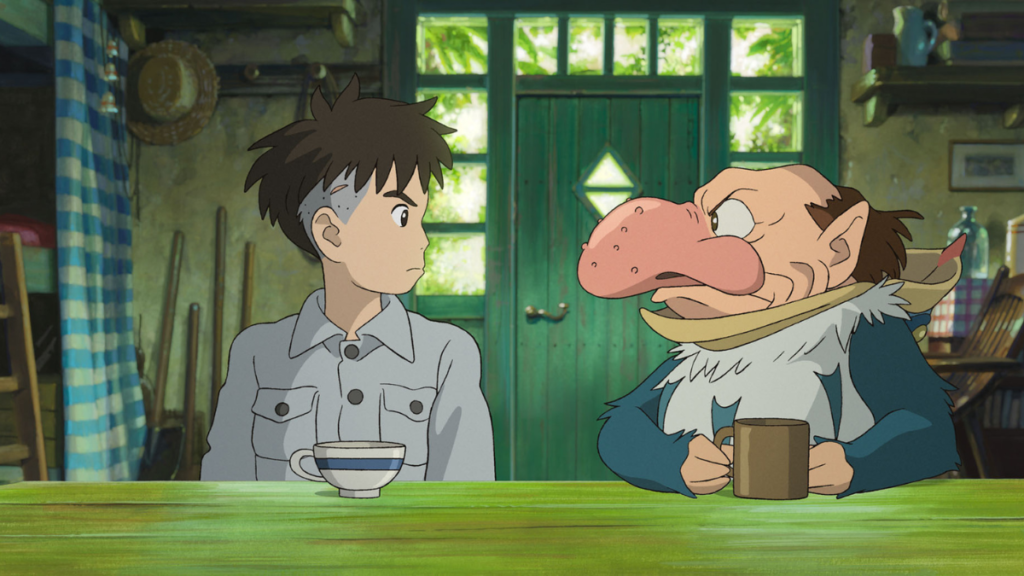

It is in this new setting that the central character encounters a heron, a half-human and half-bird hybrid claiming that Mahito’s mother is still alive. The heron propels Mahito into an alternate plane where new souls emerge and departed souls find solace.

Deviating from its original Japanese title does not diminish The Boy and the Heron‘s exploration of its fundamental philosophical question: How Do You Live? Miyazaki strives to capture the comprehensive essence of the perpetual, indifferent, and inevitable cycle between life and death.The characters in the film respond to this existential dilemma, showcasing diverse coping mechanisms in the face of their unavoidable mortality. The heron, embodying a disdain for death, behaves selfishly and antagonizes Mahito. Meanwhile, Mahito perceives the heron — and everyone navigating the complexities of life — as an individual in need of assistance.

The Magic of Animated Life

The Boy and the Heron, at first glance, seems to tread familiar artistic territory, echoing the visual style of Miyazaki’s past creations. Yet, beneath this initial familiarity, the film swiftly reveals the distinct evolution of Miyazaki’s artistry, marking a departure from his established norms and setting the stage for a new cinematic experience.

In the film’s opening scene, Miyazaki’s portrayal of the burning hospital displays a new, kinetic quality that diverges from his previous work. The scene transforms into a nightmarish sequence, with the dark Tokyo night illuminated by dancing flames and contorted faces, reflecting the horror of bombings and Mahito’s fears. While reminiscent of Grave of the Fireflies, Miyazaki’s approach aligns more closely with the atomic bomb scene in Barefoot Gen, offering a bold and potent start to the film.

Even in fantastical scenes, Miyazaki’s art evolves, building on the foundations of Spirited Away and Ponyo in movement and wonder. The Boy and the Heron is rich in movement and kineticism, evident in Mahito’s character design and actions that draw inspiration from a previous Miyazaki protagonist: Ashitaka from Princess Mononoke.

Particularly notable are the tower scenes with the Parakeets, displaying vibrant energy and meticulous attention to background elements. Miyazaki consistently introduces striking set-pieces throughout the film, showcasing his dedication to pushing the boundaries of animation and avoiding stagnation in his distinguished career.

Metaphor through Music

Miyazaki’s longtime collaborator, Joe Hisaishi, once again delivers a one-of-a-kind score. Miyazaki recognizes the significance of granting his characters moments of solitude and incorporating quietness to allow for recovery or reflection. The instrumental solos during tranquil scenes are delightful and contribute effectively to creating a blissful or bittersweet atmosphere.

Moreover, as Mahito delves further into the fantastical world of the heron, Hisaishi’s skillful orchestration builds a growing sense of urgency, precisely adjusting volume and power. Hisaishi expertly captures the emotions of calmness, sadness, or anxiety required to tell Mahito’s story, showcasing his exceptional talent and that of the orchestra he leads.

How Do You Live?

Miyazaki skillfully integrates references in the film, including the significant influence of Genzaburo Yoshino’s 1937 novel How Do You Live? on Mahito. Juggling self-references from the broader Studio Ghibli universe and drawing from his own life, Miyazaki intricately crafts a rich and textured world in The Boy and the Heron.

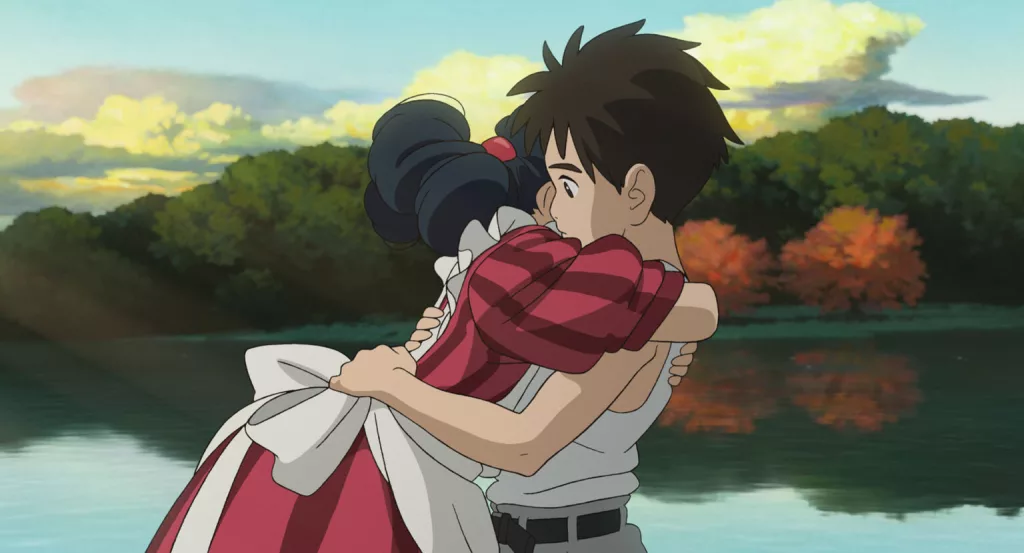

At the story’s climax, Mahito is forced to decide between crafting a new world in a fantasy realm or returning home to confront reality. The Boy and the Heron, then, poses several questions: How do you navigate grief? How do you continue living after experiencing the most profound loss? How do you traverse a world where others have moved on, and you feel stuck? How do you come to terms with the things beyond your control?

The film provides a crucial response: there’s no simple answer. Healing will occur, but it cannot be rushed. It happens in its own time, often unnoticed until you realize it has taken place. Once healing occurs, what remains is the love you’ve received, which you can now share with the world.

The Boy and the Heron requires patience, especially with its slow pace in the first hour. However, it ultimately offers emotionally impactful concluding scenes. Mahito, given the chance to govern a fantasy world, opts for the challenges of the real one — a representation of the grown-up understanding that we can’t avoid life’s difficulties. Miyazaki imparts a poignant message: embrace the real world, while using the animated realms as guides for navigating our lives.

Want to keep up with the latest Hollywood coverage? Read about the standout AAPI stars from the 81st Golden Globe Awards here!